“The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house.” —Audre Lorde

“The Kimberley Process is bullshit.” —Martin Rapaport

Author's note: This writing is part of my Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies, and Conflict Free Diamonds—a 45,000 word investigation into the dark underbelly of the jewelry industry organized by the metaphor of layered Russian nesting dolls. This section is dedicated to the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme and the Faustian bargain it struck with NGOs. As of today, every credible NGO has abandoned the Kimberley Process—and even Martin Rapaport himself has denounced the scheme as "bullshit."

—Marc Choyt

We can only get to the center of the Russian doll through a deeper exploration of diamonds.

Diamonds comprise about half of all jewelry business. And in 2016, the US made up 45% of global diamond sales, totaling thirty-nine billion dollars of revenue.

Central to the diamond business is the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme which I outlined earlier. It is the Kimberley Process, a system that involves eighty-one countries, which the jewelry industry claims certifies diamonds as “conflict free.” (In reality, it only certifies diamonds as Kimberley-Process compliant. See the words of Seán Clinton, further down in this Doll.)

[I abhore the "conflict free" narrative. Read here why I believe it is racist at its core, why we should boycott conflict free diamonds.]

The name “Kimberley” comes from the Earl of Kimberley, the title of a particular noble from England. Kimberley was the name given to the original diamond mining area of South Africa, and the first diamonds were found in deep “Kimberlite” veins—which sink into the ground like giant tubes.

Kimberley was also near the location of the first De Beers mine, named after two brothers with the last name “De Beer,” Boer farmers who had settled in South Africa. At the time, there were thousands of small-scale artisanal diamond miners.

Most of these miners were white Europeans, digging holes in the hopes of striking it rich. 6000-acre allotments were given to Boers where diamonds were found. But, as you might imagine, these lands had been occupied by tribal societies—who were stripped of their land and then used for cheap labor.

Before the South African mines, diamonds were relatively rare, and found mainly in India. The ritual of using a diamond for an engagement ring was not common, with colored gemstones being the preferred choice.

But these early Kimberlite veins were dense, providing a flood of diamonds and creating unstable markets. Eventually, the boom-and-bust diamond business of the 1870s and ‘80s enabled Cecil Rhodes, financed by the Rothschilds, to buy up all the white, small-scale artisanal miners and consolidate the diamond market.

The company Rhodes founded in 1888, De Beers, operated under the name of the Diamond Trading Company and held a near monopoly, peaking with almost 90% control of diamonds in the late 1980s. Today, De Beers operates in thirty-five countries, with mines in Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, and Canada

Making Conflict Diamonds a Virtue

Few companies in the world surpass De Beers’ public relations sophistication. The story of how De Beers singlehandedly created the diamond engagement ring market is legend in the marketing industry.

Though De Beers publicly denies any complicity in the funding of regional wars through their diamond trading, they did—as detailed in this New York Times story—allegedly purchasing diamonds from warlords until United Nations sanctions were put in place in 1998.

In fact, according to this Guardian article, De Beers has allegedly openly admitted to hoovering up warlord diamonds from Angola.

Anyone with decades of experience in the diamond business in Africa will confirm what I have been told by industry insiders: nothing in diamonds happened in Africa in the 1980s and ‘90s outside of De Beers’ influence.

For example, according to Bloomberg.com, “When Zaire -- now the Democratic Republic of Congo -- decided to sell its stones independently of De Beers in the 1980s, the company dumped huge amounts of similar stones onto the market, crashing the price. Within two years, the African nation had returned to the De Beers fold.”

In October of 1999, De Beers stopped purchasing diamonds from small-scale miners (except perhaps in Zimbabwe, as will be detailed shortly) and began to change their course.

Their strategy to deal with this damaging linkage to conflict diamonds is outlined in this New York Times piece from 2000, "Controversy Over Diamonds Made Into A Virtue by De Beers."

Like the Rae interview we went through earlier, the piece is astonishingly candid in context to subsequent events.

To start, just look how the article is framed by the journalist: the slaughter caused by blood diamonds is merely a “controversy.”

The devastation to communities, funded by the diamond trade, is not even part of the conversation. Instead, Alan Cowell, the author, seems to revel in assisting De Beers painting their houses in Ralph Ellison’s “optic white.”

Cowell starts by introducing De Beer’s “double jeopardy” dilemma: “so-called blood diamonds” were threatening the mystique of diamonds “nurtured over decades of artful image-building and brawny cartel management.”

De Beers has addressed the problem by “promoting itself as the squeaky-clean crusader for guarantees across the industry that ‘conflict diamonds’ – as they are also called – be kept out of the world of luxury goods.”

In other words, the way to deal with soiling the “mystique of diamonds” is to assure they are linking their diamonds back to large-scale mines under their control, and to brand the company as a crusader for “conflict free” diamonds. This also means no longer purchasing diamonds dug up by small-scale miners that fueled wars in the 1980s and ‘90s.

A Smoking Gun

This New York Times article lends a deeper, more sinister agenda: it hides the people with hacked off arms, the millions of dead covered in ants, their faces and limbs chewed up by animals, eyes pecked out by birds.

Instead, we have Orwellian doublespeak. “Controversy” denies complicity. (Again, I repeat: Amnesty International reports that the diamond-funded wars killed 3.7 million people. But here, this is merely a statistic.)

This article’s use of the phrase “diamonds of questionable origin” applies to the notion that the diamonds were purchased from small-scale miners, probably with the aid of paramilitaries that De Beers hired, such as Executive Outcomes.

In the 1980s and ‘90s De Beers was trying to maintain their near monopoly of the global diamond supply chain. To maintain this level of power, they needed to buy up any new supply.

Quoting the article again: “…the company’s huge accumulation of raw gems, used to control the supply and keep the world diamond prices high, had become a costly albatross. De Beer’s shrinking share of the market was making it harder to support prices by sopping up the gems itself.”

So De Beers, even back in 2000, (eighteen years before their Gemfair initiative with the Diamond Development Initiative), intends to uses “blood diamonds” as a leaping off point to “recast” a new image of themselves as “squeaky clean crusaders” to keep “conflict diamonds” out of their luxury goods.

By 2003, when the Kimberley Process was formed, the “conflict free diamonds” strategy was already well seeded. And De Beers would join the Responsible Jewellery Council as a founding member in 2004, using all its marketing talents to support this new narrative.

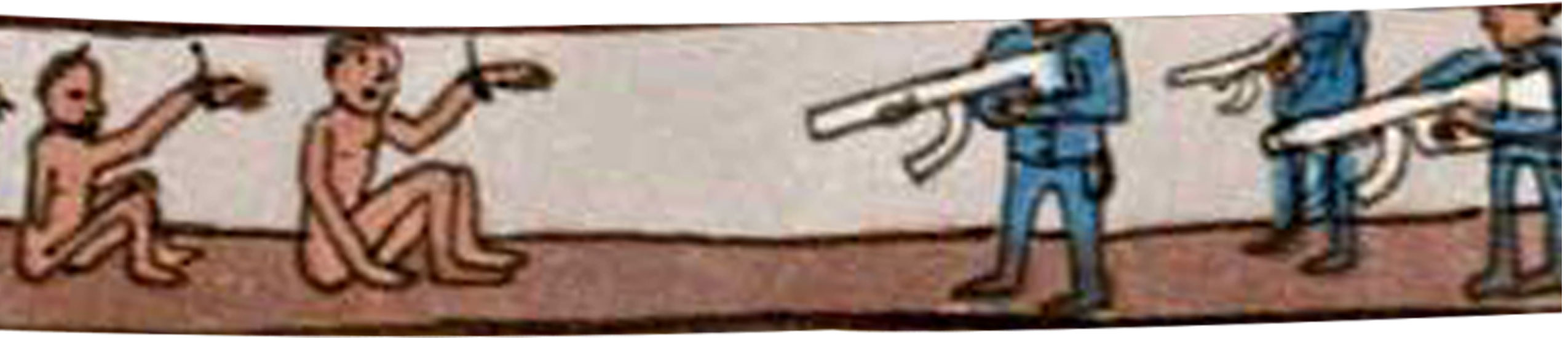

Small-scale diamond diggers in Sierra Leone. Photo by Greg Valerio.

NGO Complicity

Over the year I was working on this piece, the women’s Olympic gymnast sexual abuse story broke, accompanied by calls for massive and detailed investigations on multiple levels of responsibility.

How is it that 3.7 million people died, and the interest seems to be less?

(I don’t mean to belittle what Larry Nassar did to all his victims. But you see my point.)

Why should geography, where you were born, entitle you to certain human rights that others cannot have?

It is impossible to understand the “conflict free” narrative without understanding more deeply how the diamond sector got away with funding wars.

[Brilliant Earth, the "ethical jewelry" leader of North America, claims to be "beyond conflict free." Read my takedown here.]

The Kimberley Process was formed when Global Witness (who broke the blood diamond story in 1998) and IMPACT (then called Partnership Africa Canada, and led by Ian Smillie) sat across from diamonteers to forge an agreement which would create a framework.

Of course, the UN was involved with the formation of the Kimberley Process too—a central body representing the dozens of countries that have diamond resources.

At those meetings, some sort of Faustian bargain must have been struck.

There needed to be a system that would allow the diamond industry to prevent such conflict diamonds from reaching the market. For this to be legitimate, NGOs had to be at the table. Their participation bolstered the credibility of the Kimberley Process. They would be the watchdogs…

Essentially, the NGOs gave those responsible for the atrocities a free pass. The bargain/gamble was that this Kimberley Process would create real benefit for small-scale diamond miners while not impacting diamond sales for the jewelry sector. Underlying this approach is the broad acknowledgement that diamond producing countries need the diamond sales for revenues.

Yet, as James Baldwin said, “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.”

Had the framers of the Kimberley Process insisted on truth, reconciliation, and restitution, those who made the decision to buy the blood diamonds would have had to face diamond diggers from Sierra Leone with one arm who had lost their parents.

A truth and reconciliation process, forged in the underlying recognition of our common humanity, and restitution, would have broken the neo-colonial framework which created the blood diamond wars in the first place. What we need is economic development, support for best practices, and assistance with access to international markets.

We have seen the power of truth and reconciliation in several countries. South Africa is an amazing example of its power.

Those who prevailed in the Kimberley Process were unwilling to prioritize and form a new path outside a neocolonial framework. Case in point: miners, the victims, should have been the central voice in the creation of the Kimberley Process. But the white men in suits controlling the diamond sector would never allow this to happen. They were in control.

These events, and how they have played out, have become clear to me only in retrospect.

Yet back in 2006, no responsible jeweler would have considered the Kimberley Process an obstacle to moral veracity. Many jewelers pioneering ethical practices (myself included) held out hope that the framework might eventually take into consideration human rights and environmental issues.

It took a few more years for the Kimberley Process to show its true nature—that it was not a true starting place for a new relationship between jewelers and small-scale diamond diggers, but instead a revisionist history birthing a bogus “conflict free” narrative.

The Undermining of the Kimberley Process

The first crack in the foundation of the Kimberley Process occurred in 2011, when the member states voted to certify Zimbabwe diamonds as Kimberley-Process compliant. This was one of the richest diamond fields in Africa, with stones both close to the surface and in high concentration.

Zimbabwe diamonds are a perfect study of how high-value minerals can be a resource curse. Initially, people in the region had no idea what diamonds even were—the stones had no perceived value. In a community where children would carry bows and arrows to school in order to hunt on their way home, people were trading diamonds for meals. Yet once word got out, the community went from 100 diamond diggers to 15,000 in a period of one year.

In 2010, De Beers was accused of looting diamonds from Zimbabwe. In this 2016 article from the Zimbabwe Independent, Obert Mpofu, Zimbabwe’s former Mines Minister, also affirmed that, “De Beers looted our diamonds for 15 years and were(was) sending them to South Africa without our knowledge and they had even declared that area a restricted area, as if it was their land when the country belongs to us.”

(De Beers denies any complicity here, just as they deny any activity related to conflict diamonds.)

Once the Zimbabweans learned the value of diamonds, the resulting rape, torture, and killing is well documented. “Disappearing Diamonds” outlines the murky global smuggling method that the international community did nothing to stop.

Clearly, these diamonds coming out of Zimbabwe were blood diamonds. But they were not, technically, conflict diamonds.

This is a good time to call out the distinction between “conflict diamonds” and “blood diamonds.” Among the public, the use of the two terms is the same. Only someone deep into diamond issues understands the difference.

The term “blood diamonds” has no legal definition, but is widely understood to refer to diamonds, rough or polished, that are mined in nefarious human rights conditions, such as those just discussed coming out of Zimbabwe.

Seán Clinton, who leads an anti-Israeli blood diamonds campaign as part of the larger Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, offers a more precise definition of blood diamonds as “any diamonds that are a significant source of funding for or cause of breaches of international human rights law or international humanitarian law, i.e. war crimes or crimes against humanity.”

Either of these views casts a significantly wider net than the Kimberley Process’ term “conflict diamonds,” which refers specifically to rough diamonds that fund rebel movements in conflict with established governments. Their definition does not take into consideration human rights or environmental issues, child labor, or black-market trading.

Perhaps the most criticized aspect of the Kimberley Process is its narrow definition of “conflict diamonds,” as follows: “Conflict diamonds, also known as ‘blood' diamonds, are rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance armed conflicts aimed at undermining legitimate governments.”

Note the intentional conflation of “blood diamonds” and “conflict diamonds.”

As Clinton states, “the official KP (Kimberley Process) documents don’t even mention the term conflict free, so it can’t possibly certify anything as conflict free. There is no KP definition of conflict free. That’s a construct of the World Diamond Council specifically designed to create the illusion that KP compliance extends to cut and polished diamonds as well as rough diamonds which it does not. It’s a scam, a complete fraud and it’s a very important point to get across.”

See his thorough article on this and related issues, published on GlobalResearch.

As a further point: it’s very difficult to change Kimberley Process policy. As Ian Smillie points out while writing for the The Diamond Loupe, it was set up with “unworkable 'consensus decision-making' which allows every one of its 54 member states a veto on any proposal, of any kind. Without changing that, there will be no serious evolution."

In 2013, Ambassador Gillian Milovanovic, U.S. chair of the Kimberley Process, said at a Zimbabwe conference, “KP certification is not designed to address human rights, financial transparency, economic development or other important issues.” In the same article linked above, the author points out that “[Milovanovic] failed to add that the KP does not address armed conflict and violence when the governments are perpetrating the violence against their own people, as is the case in Zimbabwe.”

It’s also important to note that the acceptance of Zimbabwe blood diamonds into the Kimberley Process had strong trade opposition.

Even before Zimbabwe was brought into the Kimberley Process, Martin Rapaport wrote a brutal critique of the Responsible Jewellery Council. “I am severely disappointed by the RJC’s unconscionable and irresponsible failure to adequately respond to the Marange crisis.”

Michael Rae, CEO of the Responsible Jewellery Council, responded on Feb. 10th, acknowledging the issue and recommending that Responsible Jewellery Council members ensure that their supply chain does not include Marange diamonds.

(Rae did not say in his response that Responsible Jewellery Council members should only purchase diamonds that can be traced to source.)

His “recommendation” was, in fact, impossible to implement. Even before Zimbabwe was welcomed into Kimberley Process, diamonds from Marange were already being exported around the world and ending up in jewelry cases.

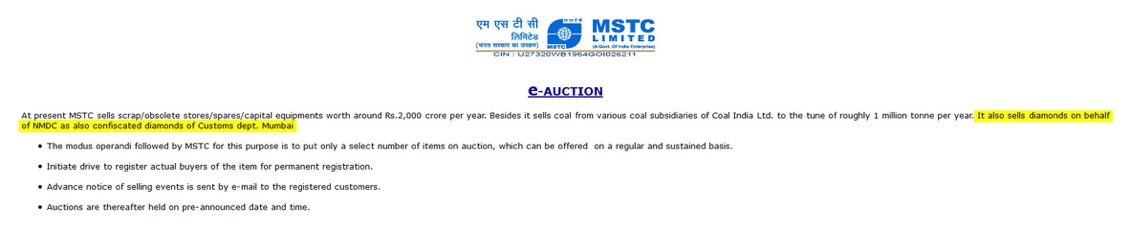

In 2011, 48,000 carats of conflict/blood diamonds from Zimbabwe, and then 10,000 more from the Congo, were seized by the Indian government. According to this article in Foreign Policy Magazine, these diamonds were given Kimberley Process certificates and auctioned off.

The website referenced in that article is still up. If you want to bid on the next lot of seized blood diamonds, perhaps here’s all the info you need!

Perhaps the money from blood diamonds still goes straight into the treasury of India. Screenshot from spring 2018.

Note the text: the government of India, though this auction, “sells diamonds on behalf of NMDC as also confiscated diamonds of Customs dept. Mumbai.”

Confiscated diamonds are those that are not in accordance with the Kimberley Process—they are essentially conflict/blood diamonds. If you want to bid on the next lot of seized blood diamonds to sell to all your friends who are about to get engaged, go right ahead!

You can even legally tell them that they are Kimberley Process certified “conflict free.”

It just goes to show that eventually, no matter what the source, all diamonds become “conflict free.”

Here’s what happened in Zimbabwe after certification:

The diamond diggers in Zimbabwe were removed from the sites where they had been working. Those who ran the paramilitary operations in Marange were soon managing diamond companies that financed Mugabe’s brutal military dictatorship. Very little of this vast wealth trickled down to the people.

The torture of small-scale diamond miners in Zimbabwe continues to this day. Here’s a current report on the Marange fields that details how 15 billion dollars of revenues taken from the diamond fields have not resulted in any improvement on the ground.

The Responsible Jewellery Council’s endorsement of the Kimberley Process’s acceptance of Zimbabwe sent the message, loud and clear: “conflict diamonds” that fund wars may not be ok, but “blood diamonds” related to human rights atrocities are fine.

But why? We have to ask.

In 2011, Zimbabwe was one of the top ten diamond producers in the world. Responsible Jewellery Council member Rio Tinto was also operating a diamond mine in Zimbabwe at the time. But this issue, I believe, is secondary.

Part of the answer lies with the Kimberley Process’ narrow definition of “conflict free”—which again, only includes diamonds funding rebel movements. Also, the Responsible Jewellery Council and Kimberley Process are aligned in terms of how they approach certification. Both rely on a chain of custody approach to ethics.

Yet perhaps the most important factor is that the Responsible Jewellery Council, representing the mainstream jewelry sector, absolutely needs the Kimberley Process narrative.

It has taken me a long while to fully hash out the implications of this insight.

Even in 2013, when I published an article on why the Kimberley Process should be abandoned, I did not yet understand that the Kimberley Process is only one strand of the diamond story DNA. (See Part 1 and Part 2 of that article, and the response that Brad Brooks-Rubin, the U.S. Special Advisor for Conflict Diamonds at the Department of State, posted here.)

The second strand is the conflict free narrative, empowered by virtually every single jeweler, and by the entire global jewelry industry selling diamonds.

Kimberley Process = “conflict free,” and the “conflict free” narrative is foundational to all jewelers who sell diamonds.

The Responsible Jewellery Council had to back the Kimberley Process, because without “conflict free,” jewelers would not have the two words that can deflect almost all concerns that ethically-minded consumers might have gained out of the negative press around diamond sourcing.

For the mainstream jeweler, the Kimberley Process’s adoption of Zimbabwe diamonds saw no public backlash whatsoever. The issue did not draw the attention to diamond sourcing anywhere near as much as the Blood Diamond film, and business as usual carried on.

Of course, “business as usual” was/is to sell diamonds at the most profitable margins possible. This is, in fact, a kind of historical continuity of how resources have been exploited for hundreds of years.

Yet we need to pause for a moment, and dig even deeper into Zimbabwe diamonds entering the Kimberley Process. What happened back then has had profound influence and birthed all-important jewelry diamond narratives which continue to shape the market.

It never mattered much to the mainstream trade that, as this article in Foreign Policy points out, up to 30% of all diamonds come from the black market, a Kimberley Process certificate is as easy to forge as an old driver’s license, or that diamond cutting is often done with child labor.

The “conflict free” narrative took care of all that.

Now, just two more points that will help you fill out the complete picture:

First, an example of how thoroughly De Beers and the Responsible Jewellery Council were intertwined, and how much the landscape has changed over the years since the founding of the Responsible Jewellery Council in 2004.

In January of 2013, the Responsible Jewellery Council appointed James Courage as its new CEO—a fitting successor to Matt Runci.

Courage worked in MARKETING!!! for De Beers from 1983 to 1996—the blood diamond years.

Such an appointment could never have been acceptable in 2006. But by 2013, Zimbabwe blood diamonds were being widely sold as “conflict free,” and there were only blue skies ahead.

Second: as I mentioned earlier in the section on the Diamond Development Initiative, in early 2018, IMPACT (formerly Partnership Africa Canada) announced their departure from the Kimberley Process.

Executive Director Joanne Lebert stated:

“The internal controls that governments conform to do not provide the evidence of traceability and due diligence needed to ensure a clean, conflict-free, and legal diamond supply chain. Consumers have been given a false confidence about where their diamonds come from. This stops now.”

“This stops now.” Really? What power does IMPACT have now that they have enabled the Kimberley Process through their participation in an ineffective program for seven years after Global Witness pulled out?

The gamble of giving diamonteers a pass for their promise of creating a valid system to protect the world from conflict/blood diamonds failed because IMPACT and their partners in the Kimberley Process even to this day have not landed on a moral footing—and only a moral footing backed up by market disruption can change what is essentially the sophisticated expression of a neo-colonial edifice.

Faustian bargain confirmed.

De Beers as an Ethical Diamond Leader

At this point, about twenty years after Global Witness exposed the conflict diamond atrocity to the world, De Beers can, ironically, claim that they are at the forefront of ethical sourcing— especially because of their GemFair initiative, a partnership with the Diamond Development Initiative. (See the Fifth Russian Doll: Death of the Fair Trade Diamond and the death of the fair trade diamond.)

In fact, this technology is foundational to De Beers’ strategy. This article on Mining.com reports that the goal is to “remove ‘conflict diamonds’ from the market” in Sierra Leone. Yet there are no conflict diamonds in Sierra Leone where this initiative is being set up.

In actuality, Sierra Leone will become a magnet for conflict diamonds from other countries. Borders are porous, and the GemFair initiative is an opportunity for small-scale miners to get a fair international price for their stones.

The blockchain-based initiative is merely the trade’s latest effort to protect their diamonds from the emerging fraud from lab-grown diamonds, and to double down on their traceable and transparent narrative which allows large mining companies to control and own the ethical diamond narrative.

The Mining.com article is also illustrative of a strong journalistic slant. They write, “Despite the establishment of the Kimberley Process in 2003, aimed at removing from the supply chain the now called ‘conflict diamonds’…, experts say trafficking of precious rocks is still ongoing.”

“Now called ‘conflict diamonds,’” and elsewhere “so-called ‘conflict’ diamonds”—just as the 2000 Times article referenced “so-called blood diamonds.” Again, a historical narrative being reframed right before our eyes.

The trafficking that is still going on, according to Mining.com, is in “precious rocks.” Precious rocks? This is new to me. Obviously, it is beneficial for the trade to distance itself from the term “conflict diamonds.” So, now we have precious rocks.

The very notion that this initiative will be “cleaning up the distribution chain” is totally absurd. There are millions of small-scale diamond diggers in dozens of countries around the world. The vast majority operate informally under government radar, and black market diamond trading will continue as it always has.

Yet Reuters can report that “De Beers, the world’s biggest diamond producer by the value of its gems, has led industry efforts to verify the authenticity of diamonds and ensure they are not from conflict zones where gems could be used to finance violence.”

Just another example of a totally coherent strategy in place for the past eighteen years. Quoting once again from the 2000 NYT article, De Beers is “…using the moral high ground for a dollars-and-cents strategy.”

Thus, Lambert’s claim that “this stops now” fails to recognize a shift in power dynamics. IMPACT is out of the game. Her words ring completely hollow. The real power that IMPACT and other organizations have is to call for truth, reconciliation, and restitution to impacted diamond communities and help build a coalition that undermines the “conflict free diamonds” in the marketplace.

We need to birth an alternative diamond story, a “truth diamond” that lets consumers know where a diamond is from and the conditions at the mine.

We also need to create fertile ground, outside of the control of the tainted diamond sector, for a fair trade diamond backed by an independent certification agency.

Continue on to the Seventh Russian Doll: Lies, Damn Lies, and Conflict Free Diamonds

Return to the Fifth Russian Doll: Death of the Fairtrade Diamond

Return to the Landing Page

**All writing and images are open source, under Creative Commons 3.0. Any reproduction of this material must back link to the landing page, here. For high resolution images for publication, contact us at expose(AT)reflectivejewelry.com.**